"The hotel is not the Hansel and Gretel-style forest hut I’d anticipated..." by Will Nett

There’s a saying in Albania: ‘D’ya know when you’re waiting for a bus… and none come along at once.’ That.

There’s a saying in Albania: ‘D’ya know when you’re waiting for a bus… and none come along at once.’ That.

How do these people go anywhere? I’d take a taxi, but I got one on the way in that was like travelling inside a Marlborough cigarette, and the traffic so congested that at one point the driver became so embroiled in conversation with an adjacent vehicle’s driver that he ended offering him a job as a mechanic.

“You could be my last fare,” the driver said gleefully, through a mushroom bomb of smoke as we eventually pulled away.

So, I’m on foot looking for somewhere to stay near Tirana on the hottest day of the year.

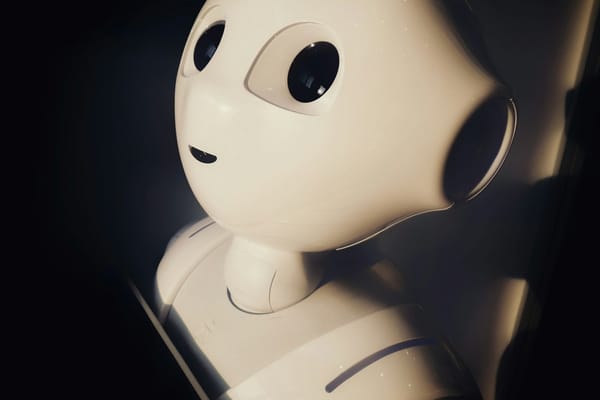

Following half a mile of roadside stumbling – the infrastructure is, well, Balkanesque – I wade through a thicket of gorse bushes to discover a small hotel in a clearing. It’s weirdly out of place… sterile- surgical-looking, almost, and not the Hansel and Gretel-style forest hut I’d anticipated. When I step into the foyer, there’s a woman – another guest – wearing an elaborate surgical support mask of pristine white plastic beneath huge black panda eyes. Understandably, she’s not for talking; she looks like she’s just gone headfirst through the windscreen of a 1988 Yugo GV – a vehicle still de rigeur in this part of the world.

I’m then passed in the corridor by who is presumably the first woman’s equally nose-fucked passenger. Or at least, it is my assumption that they were involved in the same accident. The second woman wears the same type of surgical mask, this one decorated with little Italian flag motifs. A curious place. I want to know more about what happened to them. I’m no stranger to lurching headfirst through car windscreens at a moment’s notice so my interest is piqued. I stride onto the hotel patio to see another three sad-eyed souls in the same predicament. It’s all very odd.

I’m no stranger to lurching headfirst through car windscreens at a moment’s notice so my interest is piqued.

I move off towards the car park at the rear of the hotel to think for a moment, but this area is as perplexing, hosting some racket-based beer-smuggling endeavor. Crates upon crates of various ales are being shunted around by a forklift driver who I’ve disturbed. He waves me away, then hops down from his seat, disappears briskly into a cabin, and closes the door. I snatch a posed pic for the purposes of ‘photojournalism’ and press the issue no further, in-case – like the other guests – I end up with my unmissable-in-a-punch-up Roman-statesmanlike hooter* splayed all over my grid**.

The hotel, it transpires, is linked to one of the area’s leading cosmetic clinics – and by ‘leading’ I mean ‘cheapest’ – and is hugely popular with Italian women, who routinely make the trip across the Adriatic Sea for rhinoplasty rearrangements. East Adriatic nations welcome Euros – the Italian currency – but you get a lot more for your money over the water in post-Hoxha Albania when it comes to medical matters, as the double eagle begins to spread its economic wings and usher in a boom era for tourism. No one has divulged any prices to me; having your airways severely restricted with surgical implements tends to make people less verbose, but until recently you could have this sort of procedure done for free most Saturday afternoons in my local pub by simply obstructing the TV screen while the horse racing is on.

There’s a particularly haunting Robert Aickman story called Into The Wood, about a woman on holiday in Sweden who stumbles across a sanitorium for insomniacs called the Kurhus where the inmates are treated almost like ghosts. This Kurhus of the Balkans I find myself in has all the hallmarks of a house of spirits. Nobody eats. The restaurant appears permanently empty, although my own appetite is unaffected. It is silent. Even the accompanying partners and husbands – for they are all male – say nothing, instead communicating with a series of short, nodding acknowledgements; expressions that say ‘Yeah; mine’s had hers done as well’, followed by the inevitable eyeroll. But whose standards are being aspired to, here: men’s… women’s? Collective society? And at what cost, as this Kardhasianisation culture sweeps across the land?

Despite the area’s keenness to rearrange people’s facial geography, I’ve managed to resist throughout my stay but am persuaded by an agreeably disreputable backstreet barber to have my hair cut. It’s been turning heads for no other reason than long hair on a man is virtually non-existent in Albania – presumably a hangover from the Communist days where everyone was expected to be uniformly tonsured – and I overheard one couple in a bar indiscreetly remarking on it which is what first drew my attention to how jarring it is. Having determined to grow it around two years ago until the completion of the final draft of my debut novel is submitted, it’s acquired a length that the barber – who I’ve passed most days going to and (a)fro – is relishing to get at so I let him swish the cape on my last day in town. He bursts from a cloud of self-created cigarette smoke like David Bellamy emerging from a mound of pampas grass and strops away as I quiz him on the cosmetic surgery obsession.

‘We are doing the face jobs here,” he says.

“What?”

“Like, uh; this clinic but here…” He gestures to his face.

I’m not sure if he’s joking. A backstreet cosmetic surgery clinic run out of a barbershop. In Albania.

“It is joke,” he says, taking a long drag on his cigarette.

He’s done a good job on my hair, and he knows it; I let him go to work on the beard – he’s already calculating the price in his head. It’s too outrageous for him to say aloud so he punches it into the keypad of an old Nokia phone he removes from a drawer then shows me the display. I turn my head and look at him the way Hannibal Lecter looks at Clarice Starling. The shop is decorated with sporting paraphernalia. Like all good barbers, he loves a bet.

“I’ll make you a deal,” I say...

“I’ll make you a deal,” I say; there’s always bartering to be done when travelling. Always. “You guess how old I am, and I’ll give you one hundred LEK (about 90p) for every year you’re out. And I’ll give you a clue,” I add, preening myself in the mirror, “you’ve knocked a few years off with this trim.”

I tell him if he gets it spot on, I’ll mention his name in this piece and include a photo of his work. This delights him and deters him from making a wilder guess. He squints through the smoke, his mind whirring as though his entire livelihood depends on it. He punches into the keypad once more and presents the phone. He’s played the flattery card and gone low. A three and a six; in that order. He’s eight years out. I show my passport as proof of age and shove a tenner in his hand. Who needs cosmetic surgery? Not me.

He calls as I leave the shop, “Hey; you want nose break?”

*nose

**face

Find more by Will Nett on Amazon.